The Warrior & The Weakling

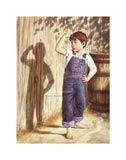

"The Muscle Man" (Jim Daly)

“There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.” (Graham Greene)

I was about ten years old at the time, sitting around a crowded Shabbos tisch with a number of my classmates and a few other orchim. One of these guests was particularly interesting. Avraham was an Israeli ex-commando turned farbrente Chabadnik. He was a tall, dark man with a long, thick black beard, a deep melodious voice, and large white teeth that spanned out across his face like a bright brick road when he smiled. His hands were large and powerful and he spoke with both a friendliness and authority that captivated everyone. He regaled us with stories about the wars, his military training, and the army life in

We, being the impressionable boys that we were, swallowed more ma’asehs than we did cholent and kugel that afternoon. Needless to say, everybody in the room was impressed by this vigorous and engaging gentleman, who in spite of having a promising future in the Tzahal or in secular life, chose to dedicate his life to Torah and Mitzvos. The stories he told that Shabbos gave us all a little glimpse into a world we would likely never come to know on our own, albeit in a romanticized and no doubt equally sanitized fashion. I suspect there was a great deal of subtle eye contact and nodding from the ba’al habayis directing our orach as to which details to include, which others to omit, or when to conclude a particular story. In any case, the afternoon was an inspiring event.

Now, imagine yourself being a very naive, or at least a quite entertained and happy ten-year-old boy in the presence of this Davidic-style ‘hero’ and in the company of friends. You are even fortunate enough to be seated right next to this ‘giant’ in the hope that some of his popularity and confidence rubs off on you. Then, something quite unexpected happens that changes your life forever, and at a mere ten years old, you would never have known such things as possible.

In the middle of one of his stories, Avraham turns to me, grabs my left arm, rolls up the sleeve of my best shabbosdike hemde, nearly tearing it in the process, and proceeds to compare his well-developed Israeli commando arms with those of a ten-year-old Chasidishe kindt! Everyone at the table laughed as I struggled to get my own arm back and out from Avraham’s vice-like grip, exposing my ‘puny’ and untrained ten-year-old muscles to everyone. To this day, I do not have any clue why he would do such a thing. I know now that it wasn’t personal, because he didn’t even know my name and there was equal odds that Shabbos of any of the other boys sitting close enough to him to have suffered this indignity as well. Yet, at ten years old, being shamed by the fellow who was everyone’s hero, and not to mention befarhesya, was a crushing experience. I swallowed my pain at the time and played along, but that event changed my thinking, and perhaps contributed in some way to my leaving Yiddishkeit. It is safe to say that none of the others present that Shabbos afternoon, including the muscle-bound Avraham, even remembers the incident. The whole affair took less than thirty seconds of their time.

Now, when I say that this event ‘contributed’ to my Apikorsis, it really had nothing to do with ad hominem issues with other frumme Yidden. People will be people, and knowing as much as I do about human psychology and development, I find it difficult to blame people for being human. In fact, the incident really had nothing to do with Yiddishkeit at all either. It was something much more personal. Until that moment in which Avraham exposed me to the as a weak and puny little boy, I had no idea that I was weak and puny! Avraham’s actions, perhaps motivated by self-aggrandizement (that wasn’t required to impress anyone there), or just anxious to be funny, made me painfully self-aware of my own physical weakness and vulnerability. Until that time, I never worried one bit about exercise, muscles, self-defense, or personal security. I became exposed as a weakling to the entire world and, worst of all, to myself.

(Had Avraham later apologized to me or displayed some gesture of friendship, this matter would have faded even from my own memory, having no lasting ill effects. As it is, the likelihood that today, were he asked of it, he would deny ever doing such a thing in the first place adds insult to injury.)

Being a Chasidishe yingele, whose mission in life is primarily to learn Torah and do Mitzvos, having large biceps should not be a requirement, even when that boy eventually becomes thirty. Yet, I left that shabbos tisch thinking about one thing and one thing only; how to make it so that I would never be ridiculed or vulnerable again. I would do everything and anything to that end. Never again would anyone grab my arm, my leg, my hand, or my attention without getting a good fight in return. If you doubt me, give it a try.

What does this have to do with leaving Yiddishkeit you ask? Directly, nothing at all. Indirectly, it began me on a course of action that would lead me away from the coziness of the communal bond. Here I am, this ten year old pisherke who has already lived through more trauma than most adults, and in the public presence of those who I like and the one everyone holds in high esteem , and I end up insulted and ridiculed over a thing I knew nothing of and could do nothing about. How much would that have affected your outlook on life? This event, insignificant as it appears, snowballed into something much larger as time went on. Nothing causes more change in the world than a changed mind, and mine had been altered profoundly.

I began then to exercise a little. I started by doing a few push-ups and sit-ups in my bedroom. Then I filled an old suitcase with seforim and started weight lifting with it. Then I discovered a durable pipe running across our basement and began doing chin-ups, and then shadow boxing. Then I found a book on martial arts in a used bookstore. It is easy to surmise as to where this was leading. Now, I wasn’t getting big muscles yet, or picking fights at yeshiva. My mind was not set upon conquest, but on active resistance. I became resistant and defensive, and in turn, less trusting; should it be revealed that my efforts at self-protection were not successful enough to repel a punch, grab, or even an insult. This development reinforced my already strong tendencies for seclusion and privacy. I managed to take on the bullies and made a few of them regret pressing me into action, in spite of my own self-doubting.

This impulse continued into my adulthood and, even well into my marriage and college education. I remained clueless to its ultimate source and, for the most part, still processed many things through the mind-set of that hurting ten-year-old child. I still had the powerful urge to study the martial arts secretively and exercise, and I found any and every excuse to do so, even if my wife and friends thought it somewhat foolish and wasteful. I could not explain to them the real reason because I didn’t know the source of it myself at the time, but I did concoct some pretty clever rationales. I hadn’t forgotten what Avraham had done, but I had never connected that Shabbos with these later events.

Subsequently, as my need for physical self-improvement increased, so did my need for information and the means to cause that self-improvement. That requirement led me to people and places outside the normal stomping grounds of most Chasidishe Yidden. I began making friends and keeping short company with people outside the religious Jewish sphere of influence. I was learning stretching techniques from dancers, submission holds from wrestlers, and healing arts from Tai Chi teachers. In yet another part of my life, I became more enlightened and more open to new ideas. I was learning something new and useful every day.

Now, I already had long-standing sefeykos in terms of Yiddishkeit (and what it claimed as truths), but until I found friendships outside of the shtetl, the close-knit world of the kehilla kept my body at home even if my mind liked to wander out. My social circle was ever widening now, even if only as a large number of acquaintances rather than close friends, and the exclusive social bonds that linked the individual with the kehilla were eroding quickly. As I said before, at the time, I had no idea this was going on or why it was happening. I reflect back and see it all too clearly now. For those who go off the Derech, there are likely to be a hundred little reasons that lead up to the major one, or as in my case, those hundreds of others offered a convenient avenue of escape.

Avraham’s actions were not a curse really. In fact, if one believes in any sort of

Avraham ended up saving me from myself. I have always lived with depression. Depression has always messed with me and messed me up at times. It makes me melancholy, artistic, creative, reclusive, thoughtful, empathetic, and stubborn to a fault. It gives me an aura of mystery that women find intriguing, and it allows me to tap into parts of my mind and psyche that others never imagine. Depression has also destroyed many opportunities in love, career, and business. Of all the things that depression does, there is one thing it cannot do, and that is provide help for itself or an outlet for its own powerful emotive force.

As it turns out, the outlet that allowed me to survive depression and to function relatively well was physical exercise. In my manic stages, rather than pacing up and down hallways or running around the house yelling and screaming, I was in the gym punching and kicking the heavy bag or skipping rope until I became exhausted; too tired to be a manic threat to anyone or anything. I would feel a bad mood coming on and stretch or breathe deeply to relax. The best part was feeling that I had done something useful with that energy. In my down times, exercise, by temporarily altering one’s chemical state through hormonal changes and metabolism, allowed a healthy avenue of escape from my doldrums, unlike many others who turned to sex, drugs, food, or indolence for comfort.

Avraham deserves gratitude for his inadvertent mockery of a ten-year-old child, though had it been any other kid, the results would have likely been quite different. I blamed him for a thing that now I can see as perhaps the greatest blessing imaginable. His actions, negative and painful as they were, were part of what held me to sanity and emotional balance. I still have my moments. I still get frustrated. That is the normal stress of life and living rearing its ugly head every now and then. Avraham taught me how to get up and be strong, and he deserves some thanks, even if he couldn’t possibly have intended it as such.

Here is what I learned from all this:

1) Do not insult or ridicule children unless you know them well enough for them to insult you back. If you make a child feel helpless, he will become withdrawn and defensive.

The traumas of youth, when placed in their proper perspective, can make stronger adults. 2)This comes about only through self-awareness. Connect the causes and effects when possible.

3) Blessings and curses raid each other’s closets for trendy outfits. It’s hard to tell which is which just by the way they are dressed. Most of the time they impersonate each other, much like mischievous twins who swap identities to confuse strangers.

4) Strong personal/social bonds are the most important factor in keeping people on the derech. A Jew can be living right smack in the middle of Meah Shearim and not have any personal connection to those around him. If he feels truly loved, there is nowhere else for him to go.

5) Thoughtfulness means that we consider the possible unintended consequences of our actions. We can’t control everything that happens, but at least we can use common sense to gauge the most likely results. Either way, we have no power over the outcomes.

6) To understand why a child is hurting, we have to look at life through the eyes of that child, and not project our own adult perspectives, thus ignoring or invalidating the child’s feelings in the process. We can’t fix what we refuse to see.

“Genius is no more than childhood recaptured at will, childhood equipped now with man's physical means to express itself, and with the analytical mind that enables it to bring order into the sum of experience, involuntarily amassed.” Charles Baudelaire (1821 - 1867)

5 Comments:

A few comments, in no particular order :

1. Good to have you back blogging !

2. Any connection between this post and 9 BeAv ?

3. > For those who go off the Derech, there are likely to be a hundred little reasons that lead up to the major one...

I think this applies equally to most important decisions / events in life. We look back and, in hindsight, identify one particular cause over 100 others, equally valid. I feel the same about my personal decision to become frum, for instance. I also read yesterday the aggadata about the churban (Gittin 55b etc) in the same light (there ! a connection to 9 BeAv :) )... I mean, did really the incident with Kamtsa and Bar Kamtsa result in the destruction ? It seems so silly !

4. Interesting you chose to quote Baudelaire in this context. I remember reading, as an introduction to his "Fleurs du Mal", how his mother used to keep the aborted foetuses, resulting from previous pregnancies that she miscarried, in pots, that young Charles would see in his home (shudder). Yes, his childhood experiences also shaped his (twisted) view of life later on...

Hayim,

Thanks for your comments.

Re:Baudelaire

What makes up who we are is for the most part unintended and involuntary. We use a little analysis to connects the dots. (I haven't read "Fleurs du Mal".)

Re: Tisha B'Av

No connection intended here at all. To be honest, I wasn't aware that it was Tisha B'Av at all! (Hope your ta'anis went well.) I had thought about retelling this little episode a few times on the blog from a a few different perspectives. After 3 or 4 tries, this is what came out.

Kamtza and Bar Kamtza is an intertesting story. Sounds like something that needs to be looked into. You'd be right to connect them. In human affairs, there is no way to know how and when an action will come back to bite you (of Klal Yisroel) in the ass.

We tend to view our actions lightly, not really thinking that a little joke or jeer won't have much effect.

Kol Tuv

Strong personal/social bonds are the most important factor in keeping people on the derech. A Jew can be living right smack in the middle of Meah Shearim and not have any personal connection to those around him. If he feels truly loved, there is nowhere else for him to go.

How humbling, yet how true. We would hope that the bonds to our faith and religion would be more tenacious than that, but in reality they are not.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home